Food Security and Climate Change

The biggest health impact and risk of global climate change is

our food security.

Malnutrition (under-nutrition with climate change) makes all other health disorders worse and more likely to be fatal.

Effects of climate change on crops is projected by climate crop computer models. Climate models don't capture many of the adverse effects of climate change on agriculture. This includes extreme weather events and combinations of adverse effects. Even so we can discern a world food security disaster from the projections at our already committed (locked in) future global climate change.

The 5th assessment changed all past assessments, by reporting that the Global North food production is highly vulnerable to climate change.

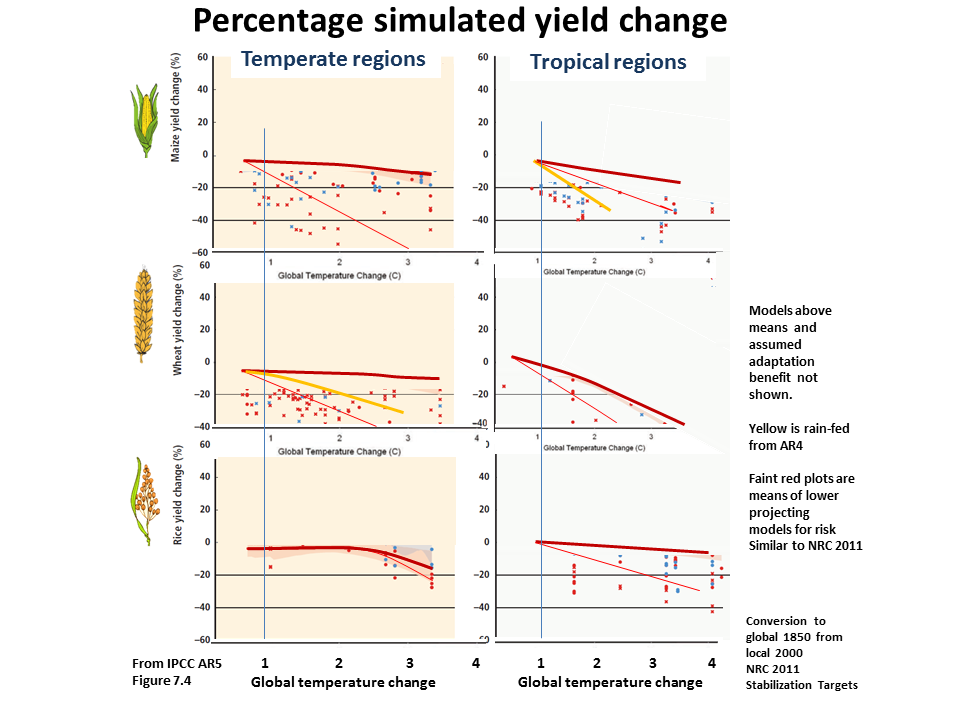

The image below is taken from the IPCC AR5 assessment on food. It is very clear that we are all in a global climate change food security emergency

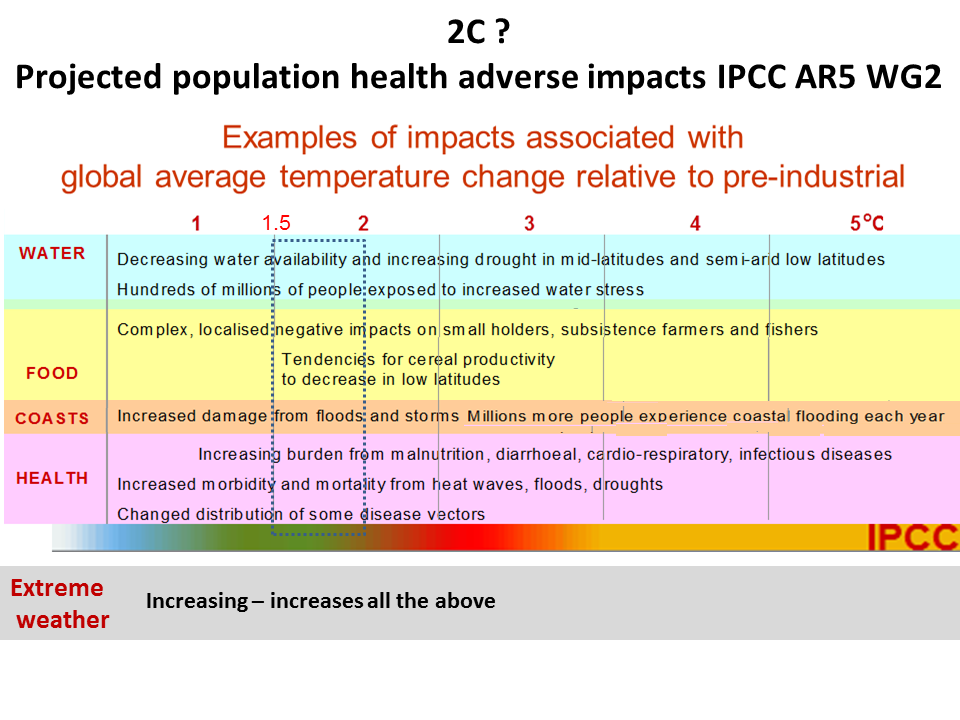

- There are already negative climate change effects to most crops (IPCC AR5)

- At 1.0C the most vulnerable regions suffer crop declines (IPCC AR5)

- Above 1.0C all crops in all regions are affected negatively, with the sole exception of temperate rice that declines at 2.0C (IPCC AR5).

- At less than 1.0C smallholders, subsistence farmers and fishers suffer losses (IPCC AR4). This Most of the world's food, and it is happening now.

- At under 1.0C most vulnerable populations suffer increased health losses adding further to losses of labour intensive agriculture (IPCC AR4, AR5)

- Above 2C all crops in all regions are in established decline (IPCC AR5) with African and US maize yields dropped 20% (NRC 2010).

A good concise climate change food assessment is the 2011 National Research Council Climate Stabilization Targets, Chapter 5 Food. It showed that assumed food production benefit for the temperate N. hemisphere was at the least questionable.

The NRC pointed out that the climate crop models, relied on for the crop yield impact assessments, do not capture many of the known large adverse effects on crops. It also questioned the assumed benefit of (necessary) adaptation, which is given prominence in the IPCC AR5.

"The expected impacts (from climate crop models) are useful as a measure of the likely direction and magnitude of average yield changes, but fall short of a complete risk analysis, which would, for instance, estimate the chance of exceeding critical thresholds-NRC 2011.

A list of adverse impacts not captured by the models from NRC (page 161):

- critical thresholds,

- responses of weeds,

- insects,

- pathogens,

- changes in water resources available for irrigation,

- effects of changes in surface ozone levels,

- increased flood frequencies,

- responses to extremely high temperatures,

- prolonged drought,

- year-to-year variability of yields."

Other adverse effects not captured are:

- erosion of coastlines and salinization inland from sea level rise, and

- erosion to agricultural land from increased droughts, storms, torrential rains and floods.

The models also do not consider the combined adverse additive and synergistic effects.

The IPCC AR4 (5.4.2.2.) said that world net food productivity is threatened at a global warming of 1.5C.

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC (2007), with less than a 1.0ºC increase in global average temperature, localized small holders and subsistence farmers, especially those in low-latitude developing nations, will suffer declining crop yields. It is interesting — and frightening — to note that in these regions, subsistence farming contributes practically all food produced, and they produce most of the worlds food.

The assessments refer to "all crops" while in fact only a few cereal crops have been assessed, most crops, including many crucial to African populations, have not been.

According to the IPCC AR5 (2014) crop models:

All crops in all regions decline with increases with warming.

- Above a 1.0ºC increase, huge populations of the most climate change vulnerable will suffer disastrous crop losses.

- Global food production is at risk at 1.5ºC

- Above +1.ºC, all crops in all regions will tip into declining yields, with the sole exception of temperate rice that declines at 2.0C.

It has been assumed by past IPCC assessments based on highly deficient climate crop models that the temperate northern hemisphere will actually benefit from global warming as a result of longer growing seasons and CO2 fertilization (excluding the many adverse effects) and only the Global South would loose out on food. On this basis it has been concluded there would be no losses of food because the Global South would buy more from the Global North's assumed increased food surplus. The IPCC AR5 shows this no longer applies. The global North from now on is vulnerable to crop losses from climate change.

For labour intensive agriculture climate change health damage and crop damage will interact negatively to reduce crop losses further.

The extreme weather events, because of their very nature, are not captured by the climate crop models, making the model results that are relied for assessing food security unrealistically optimistic, particularity for the Global North and so dangerously misleading for world food security.

Even in the most highly mechanized agricultural systems, food production is very dependent on weather. Concern about the potential

The National Research Council's chapter 5 on Food Production, Prices, and Hunger explains:

- that higher CO2 levels are beneficial for many plants, but the proposed net effect on yields doesn't take into consideration the many adverse impacts of climate change (higher air temperature, less moisture in the soil)

- that crops develop more quickly under warmer temperatures, leading to shorter growing periods and lower yields

- that the magnitude of local warming per degree of global temperature increase is a source of uncertainty in modelling

- that "it will be increasingly difficult to generate varieties with a physiology that can withstand extreme heat and drought while still being economically productive"

- that the effects of climate change on livestock, aquaculture, and fisheries must also be considered, and these are multifactorial

- that the implications of climate change on hunger or food insecurity "follow in part from price changes, but also depend critically on how sources of income and other aspects of health are affected by climate"

- that unintended consequences could have huge impacts; for example, "climate-induced changes in the incidence of diarrheal and other diseases [could] inhibit food security by reducing utilization of nutrients in food"

Food insecurity is the single greatest danger of climate change to vulnerable human populations and indeed to all humanity. That is because there are multiple adverse impacts of global warming and climate disruption on agriculture — and all of these impacts will increase as the global temperature increases.

Healthcare professionals are well positioned to keep reminding the global community about the importance of integrated risk assessment when modelling the impacts of climate change on food security.

Return from Food Security and Climate Change to the Homepage